“Is it fair to say that you spent a significant amount of time, if not six full years, at least four full years on such intangible development activities?” asked the IRS litigator.

“Yes,” answered Karen Wu.

“Yet, as a result of your activities, there were no valuable intangibles at MSell-US?”

“Dr. Rogers, my expert, was referring to process intangibles in her testimony. When I left MSell-US, we did not have a formal process for vendor relationships and sourcing. It was all in my head,” pointing at her head, she paused for a sip of water. Jay MSell Tax Director] was mesmerized by her fluency in handling the IRS litigator, and the beauty of her sparkling eyes, and dark shiny hair.

“I believe, if I remember correctly, Dr. Rogers stated that our transfer pricing fairly compensated MSell-US for pre-existing product selections and vendor relationships,” she continued. “So, again, I do not see a contradiction. Going back to my analogy, before we took a formal approach to our intangible development process, we were able to grow a lot of delicious apples, but we had no tree.”

MSell’s transfer pricing advisor, Corrine Rogers, skillfully built a sandbox for the IRS and the company began to play in, based on the so-called Income Method, as the litigation moved forward.What Corrine came up with was an analysis along the following lines:

- Build the cash flow under the old business model, taking into account the fact that MSell was heading into a period of decline. Although such projections were not produced at that time, she worked with Amy for a couple of days and pieced together the evidence on declining same store sales, and spend per customer, despite the increase in average price per SKU. She discounted this cash flow by the industry average Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC), plus 200 basis points, based on the argument that specialty retailers of non-necessary, impulse purchase retailers were subject to a higher cost of capital. She substantiated her point by making WACC comparisons between (i) general merchandisers and specialty retailers; (ii) larger versus smaller retail chains; and (iii) value versus upscale retailers. All of these comparisons yielded a higher average WACC for the latter categories by about 200 basis points. The discount rate she used was 13 percent.

- Use the actuals and projections to build the cash flow under the new business model from 2006 onwards. She used a lower discount rate for this cash flow. Under the new business model, MSell-PRC was effectively guaranteed a 7 percent operating margin for MSell-US. Therefore, MSell-US’s risk was the credit risk of MSell-PRC. Accordingly, she ran faux-rating8 analysis of MSell- PRC on a stand-alone basis, and concluded that the cost of debt for MSell-PRC over the period would be 5 percent. She used this 5 percent discount rate to calculate the net present value of MSell-US’s profits under the new business model.

Mr. Siegel had explained that the Global Principal company would be the one designing or selecting the merchandise, getting it manufactured, and supplying the merchandise, as well as everything else necessary to operate the local stores (such as store layouts, promotional and advertising materials, merchandising aides, and manuals). The Global Principal would act as the heart of the enterprise, housing a critical mass of executives with global responsibilities. All other details about where it would be incorporated and its operational details were to be designed if MSell decided to move forward with the plan.

Karen Wu had been skeptical about this approach, but she put in an effort to understand how it would work. Here is what she concluded:She was surprised that tax-planning decisions were like any other business decision. AsMSell’s CEO, Karen had always been under the impression that she only had to worryabout running a successful business and Mr. Siegel or someone else would calculatethe least amount of tax payable under the applicable rules. Now she realized that thiswas not the correct framework to apply for tax planning. Like any business matter, shehad to make choices about taxes today and live with the consequences going forward. While MSell hesitates with the global tax restructuring approach, they go ahead with a state tax planning idea of putting intellectual property (“IP”) in a subsidiary located in a lower tax state, which was quite popular in the late ‘90s. As Jay, MSell’s Tax Director, confers with his friend, Jeff, his one-time colleague with strong technical skills who now works for Diversified Industries, he realizes there is nothing simple in transfer pricing – especially if you want to do it right.

“The so-called net royalty approach is really a convenient short cut, but I do not think it is the best planning tool,” commented Jeff, “the essence of the arrangement is that the IPCO [the subsidiary corporation to which the IP has been contributed] engages the parent company as a contract development services provider, typically on a cost-plus basis, or a different basis but always as a no-risk, service provider. What matters is that the IPCO separately pays for future development, so you do not need serial IP contributions.”

“Look, Jeff. We don’t need to continue discussing this. Tell me what else is going on at Diversified Industries.”

“No, you have a good question and I want to answer it. My advisor had once told me that my concern was a §1.482-1(d)(3)(iii)(B) issue. So I said, ‘what exactly is that section of the regulations?’ He explained that that section related the allocation of risks and determining whether an entity that is supposedly assuming a risk really assumes it. According to him, this section of the regulations is the ‘heart and soul’ of transfer pricing. Apparently, the U.S. Treasury had the same concerns as I had and wrote this piece of regulation as to the type of arrangements that the IRS will respect as a bona-fide assignment of risk. In our case, we are really assigning the risk of maintaining and developing IP to IPCO which, in turn, engages

OPCO to do most of the heavy lifting. This piece of regulation suggests that IPCO should also be doing something and defines what that something would be.”

“What is it?”

“The regulations allow taxpayers to allocate risk as they see fit as long as the party assuming the risk, in our case IPCO, has a meaningful control over the risks, and either documents or consistently follows the intended risk allocation. Additionally, IPCO must have sufficient resources to fund the operations and absorb any losses resulting from the assumption of risk. The main point is what kind of control IPCO can have over the IP development or contract management unless it is sufficiently staffed.”

Distribution transactions? Simple! Just slap on a CPM/TNMM! “Not so fast,” says Erik, young, intellectually curious, and enterprising country manager for Canada. As he realizes that the tax director, Jay, is only tangentially interested in evaluating different options available to them, he takes it on himself to educate himself in transfer pricing. Here are his notes:Real World Box 5.1: Erik’s Notes on Canadian Transfer Pricing

Q: What are the options for MSell-Canada’s transfer pricing?

Three options:

-

Use external benchmarks (TNMM). Select comparable companies: independent retailers, with public financials (SEC 10-K filings). Calculate the comparables’ margins. Set our transfer pricing to target their profitability. Must have our projections to set prices, but adjustments can be made.

-

Resale Margin Method. Benchmark controlled retailer’s margin (MSell- Canada) based on its direct purchases from unrelated suppliers. MSell-Canada may buy directly from third party vendors. Need comparability on type and range of products, volumes, warranties, and payment and shipment terms. Usual problem with this approach: direct, uncontrolled purchases usually cover only marginal or complementary products and would be in smaller volumes. MSell-Canada may also do more, such as design, selection, sourcing, for direct purchases. This would only rarely work.

-

Use wholesale prices – Comparable Uncontrolled Price (CUP) or Cost-Plus Method. Benchmark the supplier’s prices or profit margin based on your supplier’s sales to unrelated retailers. But MSell-Canada must be similar to those unrelated retailers (probably! Unrelated retailer customers are all department stores). Adjustments are possible for some differences. The most common issue is that unrelated customers would often be in different markets (our case,too: U.S.A. versus Canadian markets also they have their own stores names and other know-how intangibles). Benchmarking price or margin? CUP is more cumbersome. Cost-plus more practical (but resale margins may be too disparate).

Q: What are the implications for MSell-Canada’s commercial risks?

- Least risky is the TNMM – targeting a profit margin for every year. May exclude restructuring and non-operating costs, but MSell-Canada would end up turning a profit every year. But will probably be a lower level of profit then others.

- Next is resale margin. The benchmark would be at gross profit level. MSell-Canada will have risk with respect to the level of its operating expenses.

- Riskiest is the CUP/Cost-Plus. MSell-Canada will pay, on average, the same price as department stores, and more for other adjustments, and will make a profit or loss depending on its resale prices. In the long-run, this may generate the highest level of profits for MSell-Canada.

Q: Which one the tax authorities like best?

They love the simple approaches that leave more profit in the local country. They all want to see profits. Either explicitly, or implicitly, they will test to see if your profitability is consistent with TNMM levels (even if you use resale margin or CUP method).

While Jay dismissed Erik’s efforts as an academic exercise, and chose the TNMM as a simple, practical method everyone else uses, he came to regret that as they come under audit by the Canadian Revenue Agency.Jay finally got hold of the proposed CRA adjustment, as well as his notes from their earlier discussions, and he opted to speak with Bruce Balaban about it. They reviewed the arguments as to why the wholesale price between MSell-US and unrelated department stores may not be used as a benchmark for presumed sales of the same merchandise from MSell-US to its Canada branch: department stores sold other stuff and purchased MSell merchandise to complement what else they are selling; and department stores had their own administration, systems, trademarks, and just purchased the merchandise. However, MSell-Canada only sold MSell merchandise at its stores and received marketing, general, and administrative support from MSell-US. “We can argue the differences all day,” commented Bruce Balaban, “but we cannot convince the CRA unless we take their approach and propose our comparability adjustments. And, then, they will probably not accept all of our adjustments, but we will have reduced the final adjustment before we take it to competent authority route.”

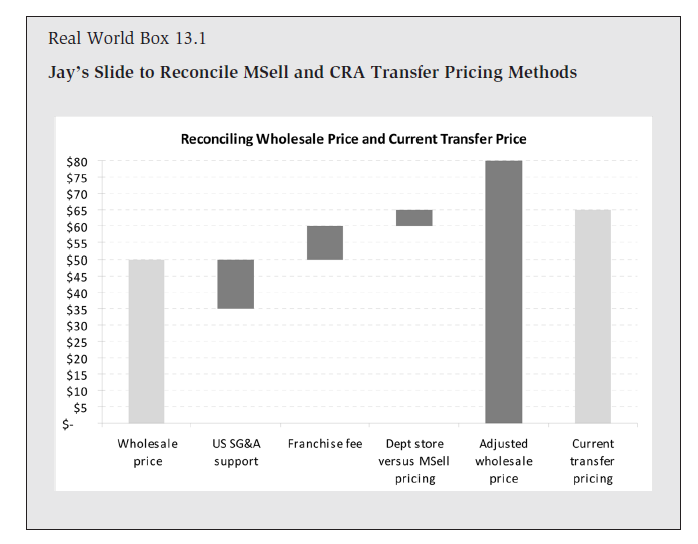

After a few meetings and back forth, Jay finally tried to reconcile the two approaches (as seen in the table below) with the help of his advisors. Most readers will notice that the chart was misprinted, the three steps in the middle should have been level with the left bar at the bottom and the right bar at the top. Armed with this table, Jay was able to show that MSell-Canada would not have done any better by going the CUP route – i.e. MSell, Inc. selling to MSell-Canada at the same prices as it sells to third party wholesale customers. With this table, we try to dispel a common belief that if you have a comparable uncontrolled price, then your transfer price should be equal to that price. This is not necessarily true because there are some very common differentiators as outlined in the graph.

Armed with this table, Jay was able to show that MSell-Canada would not have done any better by going the CUP route – i.e. MSell, Inc. selling to MSell-Canada at the same prices as it sells to third party wholesale customers. With this table, we try to dispel a common belief that if you have a comparable uncontrolled price, then your transfer price should be equal to that price. This is not necessarily true because there are some very common differentiators as outlined in the graph.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.